Our experts and industry insiders blog the latest news, studies and current events from inside the credit card industry. Our articles follow strict editorial guidelines.

In a Nutshell: Artificial intelligence and robotics have analysts spooked about the future of work because AI seems to threaten the kind of non-routine, creative jobs people have always invented when technology replaces manual labor. But AI’s prospects aren’t a mere question of supply and demand — global geopolitical and regulatory factors complicate the picture. At UK economic intelligence provider Fathom Consulting, Deputy Chief Economist Andrew Harris views AI with caution and as an opportunity. With proper planning, he argues, the global economy may be on the cusp of a significant, positive reduction in work.

If you’re into economics, you may remember the story about the preeminent British economist John Maynard Keynes, who famously predicted in 1930 that people would work 15 hours a week within a century.

In Keynes’s vision, technology and innovation would increase productivity by such a measure that prudent planning and social consensus would result in a drastically reduced need for work.

Any way you look at it, it’s a safe bet that the global workforce won’t achieve Keynes’s 15-hour goal by 2030 — far from it. The reality, at least so far in modern economic history, is that workers have only reduced their hours a little and are perhaps more keen to get compete and “get ahead” than Keynes predicted.

But Keynes may have been onto something all along, according to Andrew Harris, Deputy Chief Economist at the UK economics intelligence provider Fathom Consulting. He just didn’t get the timeline right.

A group of Bank of England economists broke away in 2003 to form Fathom at a time of extensive siloing in the bank’s thinking about the relationship between people and money. Economists and finance professionals rarely communicated; when they did, they spoke a different language.

Fathom aims for a more holistic, consultative view of the complex interactions of macroeconomics with financial markets and geopolitics. A global client base turns to the Fathom team for expertise in pensions, property, finance, politics, banking, economic modeling, and climate economics.

That comes in handy when looking at the future of work. Harris said AI’s unprecedented reach into highly productive, non-routine jobs may finally prove Keynes’s theory of productivity works in practice.

“In many studies on the backward-bending labor supply curve in economics, there comes a point where if you offer people more money, they want to work fewer hours,” Harris said. “Keynes may have gotten it wrong by a few decades, but that’s the route we seem to be taking.”

Why the Fourth Industrial Revolution is Different

Whether you regard that with dread or anticipation depends on your point of view and your sense of optimism. It’s important to recognize an ongoing downward trend already exists.

In the US, for example, momentum toward a four-day, 32-hour workweek continues in 2023. In Keynes’s academic heyday during the Great Depression, that would have been a pipe dream.

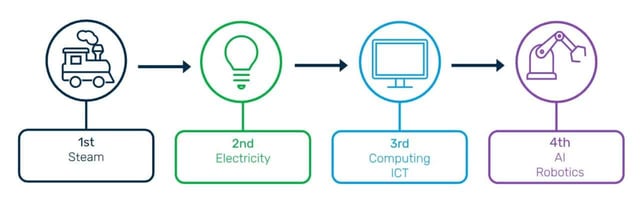

Meanwhile, economists generally regard the arrival of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and robotics as the modern world’s fourth industrial revolution. Crucial differences in the character of the transformation are essential to assessing AI as a genuine harbinger of fundamental change.

The traditional view in economics has always been that technology doesn’t replace aggregate jobs in the long run. Because it never has — more people are employed now than ever.

But many job categories have indeed disappeared altogether. Harris’s favorite example is the job of elevator operator, briefly essential until it wasn’t.

“We all know how to use elevators now,” Harris said.

AI’s essential difference is its reach into non-routine work, both manual and cognitive. In the first industrial revolution in 18th-century England and the second in 19th-century America, technology never rose to the height where it could replace the creative improvisation of humans facing new challenges.

Even during the third revolutionary cycle, the information and internet revolution of the 1970s and beyond, innovation has never reached beyond routine cognitive tasks such as scanning data and making simple calculations.

Only AI promises to mimic human decision-making in novel circumstances. Melded to ever-more agile and responsive robotic technology, AI may finally put non-human capital in a position to gain the upper hand over all forms of work.

“AI is exciting, interesting, and terrifying all at the same time because maybe it can compete for those jobs,” Harris said. “We can’t say for certain, but we can’t rule it out either.”

Technological Progress, But Uncertainties Abound

The terrifying problem is that inventing new forms of non-routine cognitive work has always acted as an incentive for creative destruction and an escape hatch for obsolescence.

To be sure, individual workers experienced displacement, but the labor market gradually evolved as society supplied workers trained for the available jobs. AI potentially stops that.

“The big question is whether we can get to a level of representation of generalized human cognitive abilities known as artificial general intelligence or AGI,” Harris said. “We’re not there yet, but that could change.”

Fathom reaches clients in three ways. Through its Global Outlook, it contributes intelligent, independent, data-driven quarterly assessments and in-person presentations to global subscribers. Fathom also provides consultancy services to clients needing the broadest perspective for making mission-critical decisions. Underlying both are extensive data, modeling, and tools to organize disparate inputs into a coherent whole.

It’s an ideal foundation for judging whether AGI is even possible. For Harris, the question is still open. But there’s no doubt AI has made phenomenal progress with the rise of ChapGPT and other generative technologies.

“Achieving true AGI is very hard to predict or even think about,” he said. “But the diffusion process (i.e. the time for an innovation to go from invention to widespread adoption) is getting much quicker. You can see this by looking at the pace of adoption of autos, planes, and phones.”

ChapGPT is a recent example of that phenomenon in overdrive, reaching an estimated 100 million monthly active users in two months. The point is that when AGI, or something like it, arrives, workers may suddenly no longer have a place to go.

“When we get to the point where AI has a real impact on the economy, it could happen much quicker than people think,” Harris said. “ChatGPT is relatively new to the market, but everyone’s thinking about how they can use it.”

Prospects for a 15-Hour Workweek

This is where Fathom’s synthesis of macroeconomics, financial markets, and geopolitics comes to the fore. Harris can imagine a world in the far future where there aren’t any jobs, period. Any world in which technology replaces specific jobs makes certain people effectively unemployable.

“What that potentially means is an incredibly unequal society,” Harris said. “People always expect that technology will tip the balance in favor of the owners and away from the rest of the economy.”

The US-China rivalry, a special focus for Fathom, adds intense competitive pressure to an already highly dynamic mix. Throughout modern history, technological innovation has increased the size of the economy. The obvious question for Harris is how governments and regulators worldwide deal with the fallout from when that’s no longer the case.

In Fathom’s and Harris’ view, the big reveal is that data consistently shows support for the backward-bending curve of labor economics. There’s a point in the productivity/prosperity matrix at which workers tend to prefer less work over more money.

If AI brings parts of the global economy to that point, we’ll all watch a new form of labor displacement in which social preferences begin to match theory and demand more intentional strategies for distributing work and leisure.

As some US jobs follow the EU’s lead toward a 32-hour week, that means we may be thinking of the problem in reverse because productivity and wealth may bring us to the point where workers will demand less work, not the other way around.

For all his accomplishments, Keynes takes a lot of hits over his prediction. But things are trending in his direction. Harris is on board.

“I think it’s a good thing if we can manage to earn more and work less,” he said. “It comes with a trade-off between leisure and spending, but if we can position ourselves where we have a lot of leisure and a lot of money to spend, that seems pretty great to me.”

![How Do Balance Transfers Work? + 5 Top Offers ([updated_month_year]) How Do Balance Transfers Work? + 5 Top Offers ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2016/04/complete-guide-to-balance-transfers.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![How Do Credit Cards Work? Expert’s Guide ([updated_month_year]) How Do Credit Cards Work? Expert’s Guide ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2017/04/how-do-credit-cards-work.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![How Does Credit Card Interest Work? ([updated_month_year]) How Does Credit Card Interest Work? ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2017/07/interestworks.png?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![What is Deferred Interest & How Does it Work? ([updated_month_year]) What is Deferred Interest & How Does it Work? ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2020/12/shutterstock_1759160015.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![“Do Prepaid Cards Work on Cash App?” ([updated_month_year]) “Do Prepaid Cards Work on Cash App?” ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2021/01/Do-Prepaid-Cards-Work-on-Cash-App--1.png?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![“Do Prepaid Cards Work For PayPal?” ([updated_month_year]) “Do Prepaid Cards Work For PayPal?” ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2020/09/Do-Prepaid-Cards-Work-For-PayPal.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![“Do Prepaid Cards Work on Patreon?” ([updated_month_year]) “Do Prepaid Cards Work on Patreon?” ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2022/06/Do-Prepaid-Cards-Work-on-Patreon.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)