Our experts and industry insiders blog the latest news, studies and current events from inside the credit card industry. Our articles follow strict editorial guidelines.

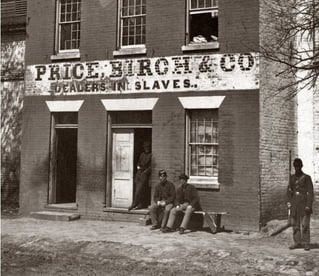

In a Nutshell: Freedom House, located in Alexandria, Virginia, began as a holding pen for enslaved African Americans waiting to be shipped to other cities to be sold during the 1800s. It was one of the largest domestic slave trading firms in the country at the time. Over the years, the building served other purposes until it was eventually used as office space. After being purchased by the state, the building was preserved as a historical landmark and currently operates as a museum. Patrons who wish to support the museum can make donations through the city government’s website.

Freedom House is a museum located in Alexandria, Virginia, which began as a holding facility for transporting enslaved African Americans and now serves as a looking glass into the country’s troubling past.

Built in 1812, the building at 1315 Duke Street was first used as the home of Brigadier General Robert Young. But from 1828 to 1861, the building served as a major slave trading facility and was first operated by Franklin and Armfield, one of the most powerful and notorious slave trading companies in the United States.

Isaac Franklin and John Armfield started their business of moving enslaved African Americans from plantations in Maryland and Virginia to the Deep South to be sold just as the cotton economy and the demand for enslaved labor exploded. Enslaved men, women and children were taken from the Chesapeake Bay area and forced to walk on foot or shipped by boat to the slave markets in Natchez, Mississippi, and New Orleans.

Franklin and Armfield used the Duke Street building between 1828 and 1836 and amassed a fortune in the slave trade transporting an estimated 10,000 people over their careers. Their business served as a blueprint for other interstate domestic slave trading companies. The building was used by smaller slave trading firms in the years that followed.

“They only operated from 1828 to 1836, so a total of eight years. But between the years of 1820 and 1840, they consumed about one-third of all money spent in the domestic slave trading industry over a total of 20 years. So you get an idea of how big this operation was,” said City Historian, Dan Lee, PhD.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, the Union Army liberated Alexandria in 1861 and used the property for their own purposes, thus putting an end to the Duke Street building’s awful history.

During that period, the Union Army used the building as a military holding facility and to accommodate the L’Ouverture Hospital for African American soldiers.

After the Civil War, the building passed through several owners and was used for various purposes, including office space or apartments. It was purchased by the Northern Virginia Urban League in 1997, which created a small exhibit in the basement for the historical museum. The building was then sold to the City of Alexandria in 2020, and the historic site is now preserved as a museum and memorial.

From Repression to a Space for Reflection

Major renovations were made to the building during the pandemic once it was acquired by the City of Alexandria. The social restrictions allowed time to reconstruct the facilities within the building so that it could become the museum it is today.

Old letters from Franklin and Armfield were collected and compiled in chronological order to piece together the history of the building in a more concise manner. The letters helped historians better understand how the business operated.

But Lee mentioned that the purpose was not about telling the story of the slave traders themselves. “That’s not really the story we want to tell. Our current exhibit is not a memorial to John Armfield and Isaac Franklin. It’s about the people who were bought and sold from this location and what their experiences were like.”

“This isn’t really about conniving slave traders. It’s about people who, at an incredibly young age, six, seven years old, were separated from their family, sent to a place they didn’t know, possibly never to see their families again. I think that’s what we are trying to capture,” said Lee.

The museum has done a tremendous amount of research and has worked with many academic historians. The Freedom House Museum currently has three exhibits: one that focuses specifically on the building, one focusing more broadly on Alexandria and how the African American community in Alexandria maintains its own history, and one on the state of Virginia and where things go from here.

While the future of Freedom House looks bright, there was a time several decades ago when the building was almost demolished.

At one time in the past, a slave named Henry Bailey was sold from the building at a young age. He was sent to Texas and, at the end of the Civil War, he walked all the way back to Alexandria to find his mother. Incredibly, Bailey found his mother living not too far from the slave pen from where he was sold. He then became a preacher in the area and helped establish more churches.

One of his children was Annie B. Rose, and Rose became a prominent activist and community organizer within the city of Alexandria. Her main passion was the care of the elderly, and an elderly care center in the city is named after her.

In the 1980s, there was a plan to destroy the Duke Street building. Rose helped raise community awareness that her father had been sold from the building. Through her effort, the building was saved and eventually sold to the Northern Virginia Urban League.

“She wanted to celebrate freedom rather than slavery and, given how strong her voice was and her personal connection to that that building, it was agreed upon,” said Lee.

“It was a desire to focus not on enslavement, but on emancipation.”

Keeping History Alive Through Patronage

As with most historical sites, the need for community support is ever present.

Lee mentioned there are a number of factors involved in the general upkeep of the facilities. “Our city bought the building and we had to get a grant for that. We had to make some significant renovations to make it ADA compliant. The city also pays the staff, but many of the other renovations and new exhibits rely on grants and donations.”

He also addressed the fact that as buildings age, they become harder to maintain, especially as the environment changes.

“Our department has a bunch of buildings that were built in the early 19th century, or even the 18th century,” said Lee. “These buildings were not built to last that long. Times have changed, the soil, especially, has changed. Time erodes what was built a long time ago.”

Those who wish to become patrons of the community and support the maintenance of Freedom House can submit donations by credit card through the Alexandria government website.

Lee said that, despite the hardships of keeping these historical sites in running order, the enrichment they provide to the local community and all visitors is encouraging. “I think one of the things about being a historian of the city is that we have an incredibly engaged audience, both our our residents, and our outside visitors.”

“We have gotten a lot of positive reviews since the reopening, both from media and visitors. We’ve had kind of an overwhelming amount of visitors,” said Lee.

The Value of Connecting with History

It’s always difficult to talk about the United States’ tragic history of slavery, and even more so when memorializing specific sites for historical purposes.

The challenge is often how to balance between remembrance and paying solemn respect. Examples like the Auschwitz concentration camp and the 9/11 Memorial come to mind. The same is true for anything involving slavery.

So while the story of the Freedom House is dark, it has been preserved because the community came together and made it a priority.

For City Historian, Dan Lee, what rewards him the most is when he sees parents going through the museum with their children explaining the relevance and magnitude of what they are viewing. “How do you approach this topic? How do you talk about how someone could buy and sell someone who was your age or even younger?”

“Overhearing those types of conversations between parents and their children really crystallizes what this museum is about, what’s really important,” said Lee.

![8 Best Credit Cards for Light Spenders ([updated_month_year]) 8 Best Credit Cards for Light Spenders ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2018/06/light.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![3 Key Differences: Chase Slate vs. Freedom Flex vs. Freedom Unlimited ([updated_month_year]) 3 Key Differences: Chase Slate vs. Freedom Flex vs. Freedom Unlimited ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2016/12/chase-slave-vs-freedom.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![12 Best Credit Cards After Buying a House ([updated_month_year]) 12 Best Credit Cards After Buying a House ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2021/06/Best-Credit-Cards-After-Buying-a-House.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![The History of Credit Cards: 2000 B.C. – [current_year] A.D. The History of Credit Cards: 2000 B.C. – [current_year] A.D.](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2020/12/shutterstock_723428044.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![11 Car Loans For No Credit History ([updated_month_year]) 11 Car Loans For No Credit History ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2023/02/Car-Loans-For-No-Credit.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![Chase Freedom vs. Discover it® Cards ([updated_month_year]) Chase Freedom vs. Discover it® Cards ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2022/03/Chase-Freedom-vs.-Discover-it.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![Is the Chase Freedom a Visa or Mastercard? ([updated_month_year]) Is the Chase Freedom a Visa or Mastercard? ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2018/03/chasevisa.png?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![Chase Freedom: Credit Limit & Benefits ([updated_month_year]) Chase Freedom: Credit Limit & Benefits ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2017/07/chasefreedom.png?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)