In a Nutshell: Accumulating student loan debt has become a typical part of higher education for students. As of March 2018, nearly 44 million Americans owed over $1.48 trillion in student loan debt, a number expected to grow as tuition rates outpace inflation and wage growth. Few people experience the hardships of student loan debt more than students of color. Approximately 77.7% of all black students use federal student loans to pay for their education. That group also has the highest loan default rates and lowest graduation rates among college students. Research from public policy organization Demos shows that nearly half of black students default on their student loans within 12 years of starting college. We spoke with Demos’ Senior Policy Analyst Mark Huelsman for more information on the topic. //

No one sets out to accumulate debt, but most financial institutions don’t consider all debt to be bad.

For example, taking out a mortgage to buy a home that is likely to appreciate in value is good debt. Borrowing to finance a $75,000 luxury vehicle that loses value with every new mile on the odometer isn’t smart unless you have the income to offset the expense.

Consumers have long considered education as good debt. And although higher education costs have increased exponentially over the last two decades, it is still considered a solid investment that pays great returns over a lifetime.

But many Americans are coming to an impasse where the cost of an education is so great that the amount borrowed starts to creep into bad debt territory.

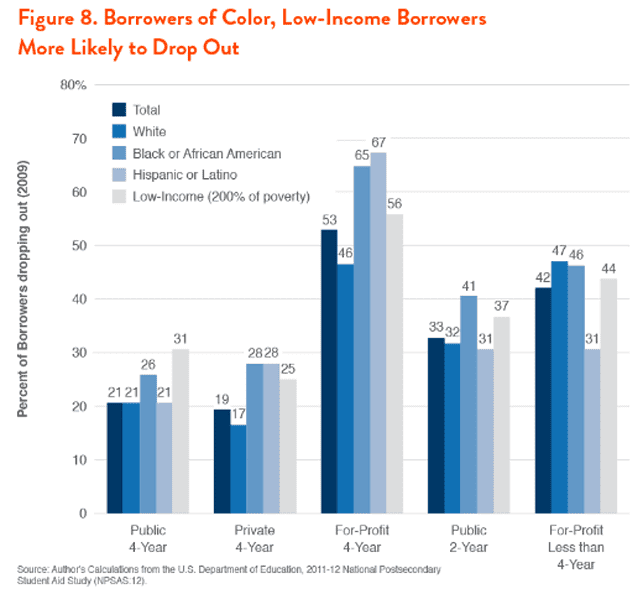

This is especially true for students of color, who statistics, show take out larger loans to complete their education and have greater default rates on their student debt.

With inflation inching upward and wage growth lagging well behind the rapid rise of tuition costs, more students are struggling to afford their college education. As of March 2018, nearly 44 million Americans owed over $1.48 trillion in student loan debt.

Those numbers are the new norm in higher education, as student debt becomes the primary way people finance education. The trend has grown as more students of color pursue a college degree, and those among them from lower income households take out loans to pay for their education.

Mark Huelsman is a Senior Policy Analyst at Demos.

Mark Huelsman, a Senior Policy Analyst at public policy organization Demos has spent years studying economic and racial inequality in the educational system. He recently spoke with us on the topic of racial inequality in student loan processing and college enrollment.

“Students of color used to make up a very small percentage of the college-going population,” he said. “In 1980, students of color made up 1 out of every 6 college students. Now they make up close to half. The shift to using student debt as the primary mechanism for financing college happened as more low-income students were coming to college.”

The debt loads of today’s graduates may seem unrealistic to college students of the 1970s or earlier, who enrolled during a time when a part-time job after class could pay for an education.

“College was a less risky endeavor for them,” Huelsman said. “Now that it’s become more important, it’s become riskier. Now you don’t have just the decision to go to college, but you have a loan repayment timeline you have to meet and pay off. We’ve thrown that at a generation of students that is more in need of financial support.”

And statistics show minorities require more of that support than white households, which on average hold a net worth 13 times that of black households and 10 times that of Hispanic households, according to Huelsman.

Debt Neutralizes Education’s Role as the Great Equalizer

Pundits say that education puts everyone on an equal footing. But when students face massive debt and monthly payments shortly after graduation, a diploma becomes less of an equalizer and more a reflection of the financial inequality we see in today’s society.

“Where that shows up most acutely is in loan repayment rates and loan default rates for students of color,” Huelsman said. “Those rates are much, much higher than they are for white students. Student debt, in some cases, is reproducing the inequality we see in our economy when it was meant to alleviate it.”

Huelsman noted that 77.7% of black students use federal student loans to pay for their education. That group also has the highest default rates and lowest graduation rates among college students.

Nearly half of black borrowers default on student loans within the first 12 years of starting college, according to the US Department of Education’s 2017 report by the National Center for Education Statistics. Among students in four-year bachelor’s degree programs in 2008, just 21% of black students graduated in four years. That number is substantially lower than the 30% of Hispanic students and much less than the 44% of white students and 48% of Asian students who graduated within that time frame.

“That doesn’t mean that college isn’t worth it for a lot of people,” Huelsman said. “College is still something we should be investing in and encouraging people to go to. But it’s become riskier for some borrowers and not others.”

Huelsman said these statistics aren’t a reflection on minorities or their ability to pay their debts as much as an issue with the historical imbalance of wealth in America. After all, more than 4.6 million Americans are currently in default on their student loans nationwide — and these are students of every racial background.

“The inability to repay loans is more a function of the job market for students and family wealth,” he said. “Some families have a backstop where they can help out in paying debts when a person’s wages drop or they lose their job. The safety net for borrowers of color is so much lower.”

Students Leave Public 4-Year Colleges with the Most Debt

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), approximately 86.8% of black students borrow federal student loans to attend a four-year public college, as opposed to 59.9% of their white peers.

Those numbers don’t reflect the similarly startling inequalities in minority enrollment in schools that have greater state financial backing and can, but often don’t, offer more scholarship money.

“One of the really tough problems in higher education is that the institutions with the most resources, whether they’re public or private, tend to enroll the fewest students of color,” Huelsman said. “Big public flagship schools are enrolling fewer students of color than the regional institutions, community colleges, or technical colleges.”

Instead, most students of color opt for regional or community colleges where tuition is less expensive, but the debt just as costly.

In 2012, the average black graduate from a public college held $29,344 in debt — more than any of their peers. Those numbers are likely significantly higher today, as the average college graduate in the class of 2016 left school owing $37,172.

Those costs become a major obstacle to graduating on time since many students become burned out from working long hours to afford the basic necessities their loan money doesn’t cover.

Some Minorities Have a Higher Aversion to Debt

While students of color are more likely to take on more debt to finance their higher education, a portion of minority households show a hesitancy to taking on debt. This debt aversion has its own effects on academic performance over the long haul.

“You see this a lot among Latino communities,” Huelsman said. “Some of these communities are hesitant to take on debt, partially because of historical factors, cultural factors, and just reasonable financial factors.”

This debt aversion could be part of the reason why Latino students borrow at a lower rate (39.9%) for public two-year colleges compared with white (46.4%) and black (62.5%) students.

“When Latino students go to school, they’re slightly less likely to borrow than you’d expect, but they work much longer hours,” Huelsman said. “That can be good for not taking on debt, but it can also be a bad thing when you mix extra work hours with a full load of classes.”

Whereas buying a house was once considered to be the biggest investment an adult will ever make, the rising cost of higher education makes college tuition a far more expensive purchase— and one that many people make when they’re barely old enough to vote.

Starting adulthood with excessive student loan debt that requires massive monthly payments can make it difficult to build a career, grow income, and achieve financial independence. In short, it can turn a good debt into a bad long-term proposition.

Advertiser Disclosure

CardRates.com is a free online resource that offers valuable content and comparison services to users. To keep this resource 100% free, we receive compensation for referrals for many of the offers listed on the site. Along with key review factors, this compensation may impact how and where products appear across CardRates.com (including, for example, the order in which they appear). CardRates.com does not include the entire universe of available offers. Editorial opinions expressed on the site are strictly our own and are not provided, endorsed, or approved by advertisers.

![21 Eye-Opening Student Debt Statistics ([current_year]) 21 Eye-Opening Student Debt Statistics ([current_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2020/11/shutterstock_674141887.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![How the Chase 5/24 Rule Works & Which Credit Cards It Affects ([updated_month_year]) How the Chase 5/24 Rule Works & Which Credit Cards It Affects ([updated_month_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2018/03/5242.png?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![15 Disturbing Credit Card Fraud Statistics ([current_year]) 15 Disturbing Credit Card Fraud Statistics ([current_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2020/08/shutterstock_576998230.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)

![11 Surprising Teen Credit Card Statistics ([current_year]) 11 Surprising Teen Credit Card Statistics ([current_year])](https://www.cardrates.com/images/uploads/2023/10/Teen-Credit-Card-Statistics.jpg?width=158&height=120&fit=crop)